till death, we persist

On our 'fear of death', digital afterlives and our entanglement with immortality.

You would think that, given death’s consuming nature and role as life’s antithesis, one would remember the day they were introduced to the idea of it. Not being able to remember is probably a good thing; it’s perhaps seen as a privilege for some. It means, possibly, you’ve only witnessed death from a distance like I have. And yet, we are all familiar with it. Or at least what we believe it to be.

I distinctly remember, however, when I came to terms with the impermanence of almost everything we hold dear. It was the Easter before COVID-19 hit. Since then, I’ve watched familial relationships dissipate and countless bodies grapple with health issues out of their control, some close to home, others further but still in sight. Then, I truly understood death; it’s simply the end. Over the years, the frequency that I think of this has increased. So does my marveling at how little we speak about it candidly, waiting only for its arrival to entertain its concreteness.

For so long, I’d heard about societies in the West being ‘death-denying’. It’s recognised that there is this inherent fear of death, yet here I was, seemingly untouched. It allowed me a certain freedom to explore and consider what lies beyond that loss of consciousness. It introduced me to the idea of legacy, false immortality, and more I want to touch on today.

fear, denial and misconceptions

When it comes to Western societies in particular, there is this assumption that our ‘fear of death’ is a prominent factor in our relationships or outlook and thus manifests in our practices and beliefs. This idea is wrapped up neatly, and we are diagnosed as being ‘death-denying’, at least by sociologists.

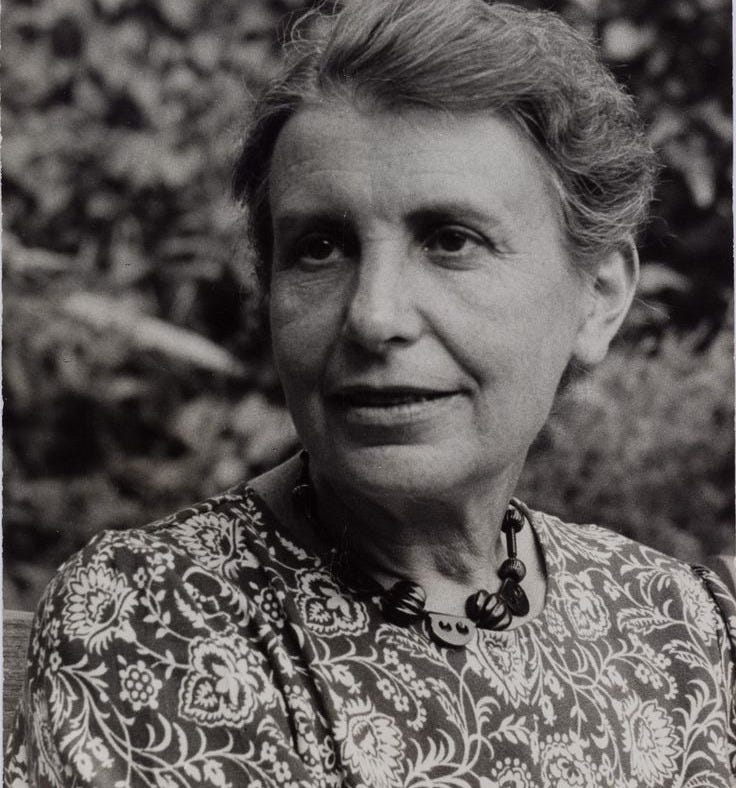

I’ve discovered through research and intrigue that some academics have a different opinion. The phrase ‘death-denying’ is an interesting one, especially due to the use of the word denial. If we want to get etymological with it, denial is a word that was initially meant for psychiatric use. Anna Freud first fleshed out the concept in her book The Ego and The Mechanism of Defense. Her definition was never fixed; it described a general result of using multiple defence mechanisms, if not the primary one. Alternatively, Sigmund Freud believed it to be about repression, whilst Dumond and Foss thought denial portrayed self-deceit. One thing they can agree on is that denial is a psychic strategy an individual undertakes. By labelling society as death-denying, we run the risk of personifying society when, in fact, society cannot be viewed in that way. A vast generalisation like this would set aside the cultural context and historical structures. When we expand our assumed definitions of denial based on how we utilise it, it becomes clear that society interacts with death differently.1

So if relying on the ‘death-denial’ label doesn’t explain our attitudes towards death in a complex enough manner, what about the ‘fear of death’ that is evident in some people’s lives? I don’t deny that fear exists, but I now don’t think it is of death for a couple of reasons. To fear something, we must know it. We can't know anything other than living, and death is purely the loss of consciousness. Logically, we cannot fear death; it is entirely plausible, however, that we fear the images of death we have constructed to fill those conceptual gaps.

Whilst we may not know death, we are arguably over-familiar with the process. We fear isolation, dependence, and disability, particularly in societies that emphasise individualism over community. Most importantly, we fear a complete and utter lack of control. It’s my explanation for the growing popularity of ‘assisted dying’, for example. We fear the images of death so much that we prioritise immortality instead. At least according to Freud, and I’m inclined to agree with him.2

immortality and legacy

Since immortality on its face is impossible, any attempt to imitate it is usually pacification. Our solution to this, in my opinion, is manufacturing legacies. It’s a concept humanity has been obsessed with, sometimes to our detriment. We see it in our monuments and statues of long-gone figures and in the paintings of families that haunt the walls of our preserved estates and national buildings. Humans are driven to leave something behind, something enduring. By creating something that lives past us, we hope to retain an element of control. The desire for immortality is not about cheating death, it’s about solidifying our presence. It dictates our choices and can quite literally change the course of history.

Consider the humanists of Renaissance Rome. They had witnessed the fall of the Etruscans and were determined not to suffer a similar fate: their culture and language were wiped out due to internal division, war and a host of other reasons. This was the humanists’ fear: “What if all their great ideas vanished with their language?”. If that could happen to a nation so close, the same could happen to them. Their legacy, the proliferation of their perceived immortality and accomplishments would all be lost if the people stopped speaking Latin. 3

Fueled by this fear, Renaissance humanists sought to preserve Latin by studying Egyptian hieroglyphics, even fabricating their own ‘neo-hieroglyphics’ in desperation. They believed that pictorial languages were the key to immortality in this sense. The prioritisation of a life and legacy they would not see makes me wonder if, to them, the death of culture and impact was worse than the corporal. If so, would conquering this fear make the inevitable easier to stomach or spur hope that they could confront that as well?

Perhaps it’s as Freud and others said: our inability to grasp death means we cling to substitutions. Here, the image of death is not that final breath but the devastation of finding you no longer meaning anything, and so the humanists were led astray with promises of permanence. Their foray into Egyptian culture and hieroglyphics did not leave the subject untouched; if anything, they muddled the art and made it more confusing for those to follow.

I cannot fault the Romans too much, not when I see how we now turn to technology to chase the same illusion of permanence.

a digital afterlife

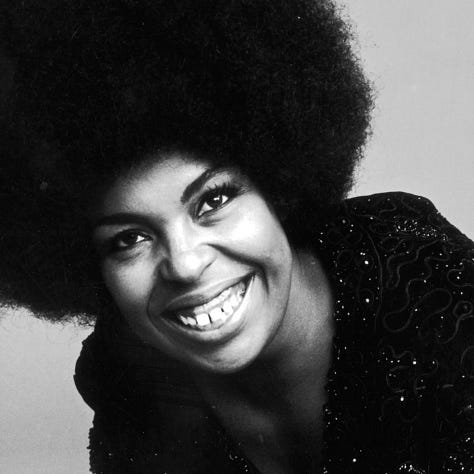

Throughout the week, whilst writing this, some celebrities have died: Roberta Flack (RF), Angie Stone (AS) and Michelle Trachtenberg (MT). Each of these was a shock, especially as I grew up with both Roberta Flack and Angie Stone’s music in my home and listened to them frequently. Quiet soon after MT’s death was announced, I began to see beautiful edits of her on TikTok with captions expressing their sadness and grief. I had sympathy; of course, I remember how devastated I was when Chadwick Boseman died. I’m still upset about it. However, after the first couple of edits, the whole thing began to feel slightly techno-dystopian or synthetic. The speed at which the edits came out was impressive, but I thought more about our relationships as viewers with creatives before and after our deaths.

My first instinct upon hearing of AS & RF’s deaths was to listen to their music, as I’m sure many fans of MT rewatched her films. It became clear that once the initial shock passed, my relationship with both artists hadn’t changed. If it had, it would only be in depth and intensity, not in-state. I had only ever known them / had access to them through their music. I still had their work in the palm of my hand. Yes, they had died, but some of them hadn’t. Of course, this is not news to many, we’ve been watching old movies and replaying tenured songs for a while now. But this kind of prolonged access is relatively new to mankind. Before cameras and tape came into play, if your favourite creative died, you could never watch them perform again. You would have to rely on your memory to evoke their image, just as their family and friends would. In a way, the advancement of technology has shielded many of us from more confrontations with grief and finality.

And, of course, with the introduction of AI, we will become even more sheltered. I recently read about AI chatbots being used to prolong the memory of deceased family relatives.4 The selective chatbots respond with only the material they're given: text messages, letters and other scripts. The generative ones quite literally take on a life of their own. Whilst the Renaissance humanists’ endeavours to ‘crack’ hieroglyphics may not immediately read as an attempt to avoid death and grief, the utilisation of AI in this way is explicit. There are a lot of ethical concerns to consider, especially when the potential to monetise such platforms arises. Then, of course, there are the dangers of having a deeply emotional connection with something that could never equally fulfil you.

While, like the Romans and the creatives, your family member’s memory could be conserved in this way, there’s an element I can’t help but consider, and that is consent. I want to ask you how you would feel if you somehow knew your consciousness, or at least an imitation, had been resurrected after your death. Would you be indifferent, or would it feel like a violation? Would it depend on by whom and for which purpose? I’ve asked myself the same question, and I don’t have a concrete answer. Probably because the thought of not being here to have a say is too big of a barrier to overcome.

So I leave you with this. I didn’t have a particularly emboldened opinion when I started writing, only a thread sparked by days of reading, but I will say this: I do think we are removed from the reality of our lives. And by that, I mean that it is a fact they will end. Our interactions with this have been moulded over time. It's partly for our survival, I guess, but it’s interesting to inspect all the same. I’m eager to see if new technologies will change this if it does at all.

Hey guys ! I hope you enjoyed this week’s essay. I went back to my research-y roots a bit with this one.

Don’t forget my new substack video series “What My Brain Eats” is coming out this Saturday with guest Philomena Marie. We’re going to discussing the media she consumes and inspires here writing. We also get into some side conversations about Trump, Gen Z, relationship and identity. More information: here.

The Wait Is Over: The Official Onyiverse Series ‘What My Brain Eats’ Is Here!

Dearest readers and soon-to-be viewers,

As per usual, you can find me on TikTok, Instagram (daily media recommendations) and Arca (curated recommendations) .

Are We A Death Denying Society. A Sociological Review

Such a well written reflection, Onyi!