All the reasons you should still love Sinners, Ryan Coogler's dedication, and the team.

the perfect amalgamation of historical references

When you think of pure, unfiltered joy, what do you think of? Of all life’s luxuries, few deliver that feeling more purely than cinema. At my best, I’m in there multiple times a month. Nothing compares to the feeling of complete immersion, even more so when I’m alone. Like music and books, there is so much to be gained from films. Whether it’s education, recognition, or simply just something to stir up a semblance of emotion after a particularly long drought.

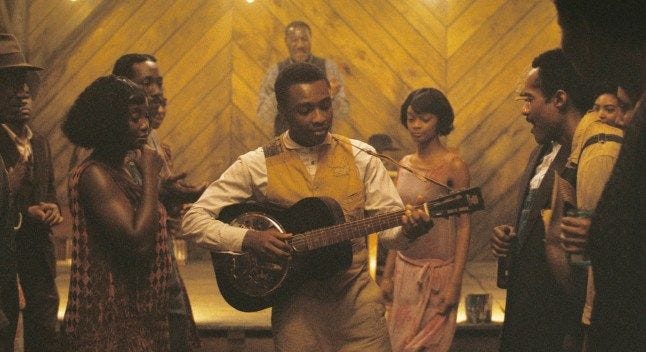

So, when I come across a film that feels as though it speaks to the very core of all the things I enjoy, history, music and just a damn good time, I have to talk about it. So today, I’m switching it up a bit, we’re going to be looking at all the reasons I love Sinners by Ryan Coogler, inspired by the incoherent notes I typed into the Notes app during and after the film in an attempt to keep them top of mind.

The Choctaw Vampire Hunters

“Nothing separates the Choctaw people from the Irish except for the ocean.”

When the Choctaw Vampire Hunters ( portrayed by Nathaniel Arcand and members of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians1) rode on to screen, I knew Coogler’s research and the film would be proof. It of course made sense that Sinners set in the 1930s would have to include Native Americans if it had any hopes of being authentic. After all, Native Americans have been there since the dawn of America, long before colonisation, settlement or enslavement.

It shouldn’t surprise any of us that Chayton and his group not only knew Remnick was a vampire but knew enough to hunt him down. They tried to help Remnick’s eventual victims, secret members of the KKK, but their help and guidance were ignored. The dismissal of Native American guidance, practices and rituals, in this film and to this day, is a deliberate choice made by many Americans. It is often to the detriment of those who refuse, governments and individuals alike. Modern ecological issues — like America’s worsening wildfires — remind us of the overlooked wisdom in Native traditions, suppressed by colonial systems.

There is, however, another connection between the Choctaw people and Remnick, the Irish vampire, that should give insight into how intentionally this film was made. In my research into the significance of the hunters being Choctaw, I learned about the unique but fitting relationship between Ireland and the Choctaws. In 1847, the Choctaws donated five thousand dollars to Ireland in an attempt to support them and ease suffering during the infamous Potato Famine. This sparked a domino effect in international relations, resulting in Ireland supporting the Choctaws during COVID and a scholarship program for Choctaw students in Ireland. This connection may seem random, but I’m immediately reminded of similar relationships or symbols of unity, like that between those fighting for Black Liberation and Palestinians. After all, the Choctaws and the Irish share a common coloniser.

The existence of this relationship, which would have started before Sinners took place, makes the Choctaws’ hunting of Remnick all the more important. Given this shared history and Remnick’s nationality, the Choctaws should have been discouraged from hunting him, unless something was seriously wrong.

The Rocky Road to Dublin

The Choctaws were right. Remnick, in all his vampire glory, attempted to lure his victims with a promise of true liberation, and he had a song to match: The Rocky Road To Dublin.

The Irish, similarly to many groups who’ve undergone oppression and colonisation — including Africans — have a history of preserving their story in song. Whilst slave songs were irrevocably linked to the horrors of slavery, resistance and hope, Irish folk songs, especially during British colonization, often told stories of loss, exile and yearning. The Rocky Road to Dublin is one of these songs. The story told in the lyrics at face value could be interpreted as a story of a man leaving the struggle in Ireland for greener pastures. In reality, whilst he left Tuam, Ireland, he was still met with violence and ridicule in Liverpool, England. If Remnick was really offering peace and liberation, there were plenty other folk songs to choose from. His victims, soon to be vampires would soon realise that although they were immortal, that in and of itself was just another trap. We see Stack express this sentiment to Sammie in the post-credit scenes. Immortality hasn’t given him peace, it’s imprisoned him.

The integration of Irish history and heritage into Sinners is yet another reason I love this film. The main vampire could just as easily rely on reputable but tired references to the likes of Dracula but Coogler and the team decided to go in a different direction. Irish history, in particular, the ways in which the British systematically carried out the colonisation and exploitation of their homeland is often forgotten if not minimised and disregarded. This film brings it back to the forefront.

The Role of Religion and Colonisation

A quick note: my aim is not to debate belief systems, but to explore how religion operates in the film.

Remnick makes a direct reference to his suffering at the height of the film, when he’s trying to kill and turn Sammie in the lake. The scene, tense but deliberate, speaks to the heart of an issue people, especially black people, would rather not address en masse: the role religion, Christianity especially, played in Colonialism.

“Our Father, who art in Heaven, hallow be they name….”. Like clockwork, Sammie recites these familiar words when faced with his imminent demise. Whilst the specifics may not be relatable to us, his motivations might be. I for one, a person who’s always been inquisitive of the history of Christianity, still find myself referring to God, but only in moments of desperation, and usually for others, not myself. You could take this as a “sign” or reason for me to rededicate myself but I see something else: the extent of which religion and fear have become intertwined and buried in most of us. Take Sammie for example, the son of a preacher who began questioning if not distancing from his father and religion to turn towards music. It’s only in this moment, I see a glimpse of his father in him, when he’s the most scared he’s ever been in his life. Some may take his return to the church in the morning as an act of submittance or surrender to God, but I see it as a return to safety. The church is all he knows but eventually we see Sammie return to music. We never see let go of the guitar, even when his father asks him to and rebuke the devil.

Christianity shapes both Remnick’s and Sammie’s arcs in subtle but significant ways. Remnick not only joins Sammie in his prayer, but does so mockingly as if he knows better. He tells Sammie and reminds the audience of the way in which the English used Christianity as a weapon. To gain control, the English systematically suppressed traditional practices like Druidic rituals. Similar could be said about the attempt to thwart what would now be considered hoodoo, voodoo or more spiritual practices. Some Irishmen were Catholics, and the English imposed Penal Laws that banned Catholics from public office and limited their access to education. This was all in attempt to promote the Protestant faith. If this sounds familiar, that would be because this was the same strategy used against Native Americans and Black slaves.

Evangelism has long been used as a disturbing excuse to cove the horrors of colonisation and oppression and those who resist are seen as the greatest threat. Take Annie’s character for example.

Are We Ever Free? (The Power of Resistance and The Illusion of Freedom)

When Annie is staked and spared from a life of immortality, we see Remnick’s true motivations for coming to the Juke and it’s written all over his face. He was after Annie’s power, not Sammie’s musical ability. So what makes Annie so valuable?

It is highly suggested that Annie is the last one in town who still actively practices her traditional spirituality likely passed down from her mother and other elders of West African heritage. Smoke teases her about her “overdependence” on the past and urges her to engage in the real world, but her reluctance to embrace modernity is the only thing that gives the group a fighting chance of warding of the vampires for as long as they did. Ironically, in his attempt to assert power, Remnick's oppressor resembles those he blames for his own suffering — by dooming his vampire offspring to the same life of entrapment instead of this rumoured freedom.

I’m reminded of how many African descendants have abandoned the traditions and spirituality only to demonise those who still practice, even going as far as to seek those out and condemn them. This often leads to the sensationalisation of events and references that are not demonic as they claim but simply an homage to our heritage. This bastardisation of our nature is evident and present everywhere I look. Watch any publically accessible documentary about Nigeria around the 1960’s and you’ll see the threads of comments lamenting over the loss of our “beautiful accents” and “classiness”. In reality the actors likely adjusted their accents to cater to white audience, their real accents slip through in prayer or in moments of relaxation. We sound the way we sound because it’s who we are, and any lusting for this specific version of ourselves is done under the cover of amnesia, not realism.

Even Smoke and Stack must come to the realisation that the path to true liberalisation is harder than they hoped, when they learn the old mill they bought was a ruse set up by the KKK in attempt to lure them in and kill them. I’m reminded of the trade agreements made after the abolishment of slavery and the beginning of the supposed end of the British Empire. Countries were promised increased prosperity, but the outcome could be seen as the continuation of the Empire and its sisters and its power under a different name. 2

fin

To me, Sinner’s isn’t just a vampire film. Sinner’s is a reclamation of history, identity, and stories that have been forgotten for too long. We see Remnick’s thirst for the power in Annie’s spirituality, Sammie’s search for purpose in music and faith and Coogler reminds that the road to liberalisation is long but worth it. This film forces us to confront uncomfortable truths through understanding and a beautiful story. This is why I love this film and I have a deep appreciation for everyone who worked on it,

Special Mention

I could write another essay about the power of the music in this film but i didn’t want to take up another 1000 words. Ludwig Göransson you did your thing!!

Hey guys, hope you enjoyed today’s essay. I loved writing about something I’m so passionate about. I’ll see you next week for another essay!!

As per usual, you can find me on TikTok, Instagram (daily media recommendations) and Arca (curated recommendations)

Don’t forget to watch this month’s episode of our show What My Brain Eats with Salome. It’s the show were I dive into my guests media recommendations, the reasons they love them (and a little gossip on the side)

What My Brain Eats with Salome

Hey guys, welcome back to another episode of What My Brain Eats with this week’s guest, Salomesdiaries!! WMBE is the show where my guests and I take a deep dive into the media shaping our lives.

The Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians are the descendants of those who (rightly) refused to leave their homeland during the Trail of Tears

Read into the investor state dispute system.

Loved this! May I ask what you meant by «Remmick's oppressor resembles those he blames for his own suffering» Who is Remmick’s oppressor? And who does he blame for his own suffering