is the body really tea if you can't eat?

Discipline, Desire, and Digital Devotion on SkinnyTok

tw: this essay will be discussing SkinnyTok and will make reference to disordered attitudes and habits without going into any detail.

Few sensations remind us, inescapably, that we are animals built of chemistry, instinct, and need. Anger is one of them. Hunger is another. Both are necessary, often impolite and, for those who suppress them, often guttural. Whilst anger finds an outlet in many ways—quietened or transformed—hunger demands to be felt and insists on our recognition for survival. Despite this, as we often do, we have found a way to commodify and aestheticise this vital physical cue, turning it into a bargaining chip. It’s a sign of, or lack thereof, discipline. Just like religious or political dogma, SkinyTok’s worship of thinness relies on a ritualistic level of consistency, harsh absolutes and community enforcement.

If you’ve been scrolling through TikTok this year, you’ve undoubtedly come across what is colloquially referred to as #SkinnyTok, a breeding ground for content idolising unnatural thinness and the disordered eating habits required to attain it. Some videos masquerade as aesthetic ‘what I eat in a day’, while others are as blatant as proclaiming, ‘My favourite thing to be is skinny’ or ‘Nothing feels as good as skinny feels’. It’s frightening and concerning, especially when you confront the hordes of impressionable kids who download TikTok every day.

The hashtag may have been banned, but the content is still circulating, with certain influencers (cough, cough, Liv Smidtch) making a name for themselves on the backs of decades of social conditioning and reinforced insecurities. Because yes, whilst the emergence of SkinnyTok may be alarming and seemingly out of nowhere, it was bound to happen, and I want to talk about all the reasons why. More specifically, I want to touch on why I believe SkinnyTok is perfectly tailored to harm women.

Good, Bad, and Edible: Food as Moral Doctrine

There’s a game I like to play with myself: how quickly can I counteract other people’s thinly veiled judgements on food before it penetrates the fortress of body neutrality I’m trying to build for myself? For every “Oh, we’re being so bad today” or “I’m going to have to run this off in the morning”, there’s an immediate “Food is neither good nor bad, Onyi, take a breath and enjoy the food”. If I don’t gamify this defence system, taking in the reality of how warped most of our relationships with food are will take its toll.

Trying to strip certain foods from the binaries of good and bad seems impossible when we begin to deconstruct years of categorisation and sometimes demonisation for a greater cause. Take the character assassination of MSG, a compound known often for its use in Chinese Food, that led to decades' worth of misinformation. Whilst MSG is generally classified as safe by the FDA, a ‘study’ released in the 60s, emboldened by xenophobia, convinced a nation of people otherwise. But why was everyone so quick to believe an unfounded study? Do not get me started on POCs in the diaspora demonising their native foods, a fairy loses its wings every time.

Even when we’re not misled by the ‘science’, the foundations for our relationships with food were laid far before we can attempt to defy them. Your religion may dictate the foods you do or don’t eat, early embarrassing moments or happy experiences inform your favourite foods and the food you avoid.

But moral judgements about food are inseparable from who can afford what, turning eating into an expression of personal politics. As the effects of globalisation played out and we gained access to imported goods, food became a status symbol. Simply put, the rich got vibrant and flavourful, and the poor got simple staples. This is where money and status become irreversibly intertwined with food. We still see it today, with expensive supplements and convenience concoctions being marketed as the solution instead of the fundamentals. We praise those who can afford it for ‘taking care of themselves’ and look down on those who can only afford ‘calorie-dense’, cheaper options.

These are the ‘harsh absolutes’ I referred to earlier, the little but impactful roles we assign food early on that dictate our health later.

The Assault on the Female Psyche & The First Conversion: puberty, womanhood and the body

So, how does all this social conditioning affect the female experience during puberty?

By the time we reach puberty, we inevitably have a slightly distorted view of food and nutrition: a mixture of household attitudes and societal views. It’s the events that occur at this stage of a woman’s life that I believe dictate her susceptibility to messaging typically seen on SkinnyTok. As we know, this is where girls, through quite an abrupt initiation, understand that they are no longer just a person, but a woman. What are the differentiating qualities that make this so pertinent to this essay? For one, it’s here that we realise that the human body is effectively a rather lovely-looking machine. Everything we gain during puberty has a reason and a future purpose, and we are irrevocably tied to it. Our bodies, now regarded quite literally as physical vessels, are also the representation of a lot of society’s thoughts and views. They are commented on, critiqued, analysed and systematically dismantled. In certain schools of psychological thought, this era is regarded as a crisis, one that initiates a quest to redefine a woman’s self-identity and how she perceives her purpose and value in life. It’s an undertaking that either makes or breaks you. This is the moment the female body becomes a site of worship and war.

When I think back on this time of my life, I’m confronted with multiple periods of instability and, quite honestly, dietary chaos. The types of food I gravitated towards were no longer dictated by what I enjoyed or how much fuel I needed, but by the perceived effect I thought it would have on my mood and body, both immediately and in the long term. It was a constant tug of war between what I looked and wanted to look like, informed by what society thought I should look like. If it sounds exhausting, it’s because it was.

To make matters worse, I was well-versed in the ‘Internet’. Here, certain influencers I regard as the high priests of SkinnyTok were thriving. Do you guys remember Freelee the Banana Girl and the rest of the fruitarians? It didn’t matter that I found their efforts and diets quite strange or perhaps extreme, even watching them out of curiosity began to influence my decisions. Because there were no regulators or mandatory fact-checking mechanisms to counteract the misinformation, I had to rely on my knowledge and intuition regarding food, nutrition, and physiology. Limited as it was, I knew enough to know there was something amiss, but the more you’re exposed to this content, the easier it is for disordered attitudes to erode your resolve. I soon found myself making banana pancakes and drinking copious amounts of tea unnecessarily. I recited the mantras of detox, the ritual of the detoxifying tea.

Digital Indoctrination: SkinnyTok as a kind of faith

That’s all it took, alongside the rogue comments on my body, for the cracks to form in my perception of self and my relationship with food. One minute you’re watching a ‘What I Eat in a Day for a Victoria's Secret Model’ and the next you’re contemplating skipping breakfast. You reward yourself with the satisfaction of knowing you’re disciplined. That’s the real punchline. You begin to succumb to the illusion of control and praise yourself for denying rather than falling for something as plebeian as gluttony. If you’re going through a phase of instability, say something as turbulent as puberty or ‘worse’, sometimes the idea of control is all you have.

This is my resounding issue with the likes of SkinnyTok: these behaviours are covertly repackaged as aspirational goals and aesthetics. By participating in this trend or so-called better way of life, you position yourself, at least to your ego, as better than or more impressive. So we arrive at a sentiment I’ve been mulling over for quite a while now: why SkinnyTok is so effective in its harm. Perhaps because it’s more than a viral moment or algorithmic glitch, but because it deploys the tactics one would associate with a new cult or growing faith we’re all skeptical of. Because of how my brain works, we’ll take it in sections: evangelism, rituals & repetition and devotion.

Cult: a system of religious veneration and devotion directed towards a particular figure or object. (the object in this case being the desired physique)

Evangelism: the recruitment phase

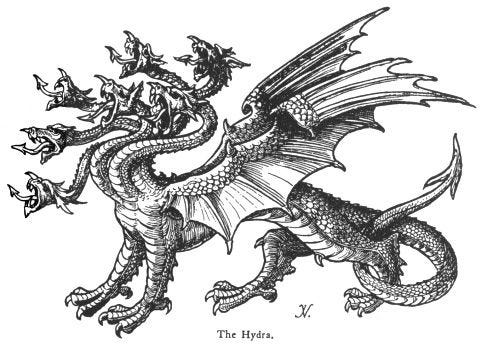

As of last week, #SkinnyTok has been banned, but this isn’t the public/mental health win TikTok may think it is. SkinnyTok is more than just a label or trend, it’s a Hydra, cut off one head and two more grow in its place: outraged prescribers who believe you’re attacking their way of life and more people wishing to capitalise on the moment.

I’ve seen many criticisms launched against Liv Schmidt defenders or avid SkinnyTok followers, and I see the reasoning, but I have sympathy and empathy. When you are led to believe something so wholeheartedly, something that becomes the foundation of your identity and self-worth, any small criticism feels like prosecution. I remember how irrationally defensive I became when other people began to notice.

The belief that criticism must warrant the fragmentation of this newly constructed identity results in a sort of evangelism, leading thousands of people to comment in defence of those who make it their job to propagate misinformation. It reads like desperation. What is the point in commenting so fervently if not to convince others of your cause? In a way, any successful overruling of criticism or ‘negative’ commentary feels like an affirmation, and the more people you convince, the stronger you feel in your stance. Like many cults, we know.

Rituals and repetition: daily practices

Having to constantly defend something you know deep down is harmful isn’t the only energy expended as a requirement of achieving the ‘perfect skinny’. Each meal becomes a balance sheet, and every step progresses towards closing a loop. There is an immense amount of calculation and restraint required not only at mealtimes but throughout the whole day. The act of measuring and weighing is monotonous and trance-like, but it is the ritual that grounds you in your beliefs. It may take many forms, but the ritualistic act is always there. Taking medicine, like methylene blue, that’s normally prescribed for serious conditions and positioning it as part of your daily supplements. Refraining from an entire food group when you haven’t been diagnosed with an intolerance. Constantly searching for the new super-drug. All these, normal in isolation but now undergoing commodification, become bizarre badges of honour, proof of your devotion to the perfect body.

Worship and devotion: a spiritual contract

Devotion may seem like a strong word choice, but that is what it is. One would only take on this level of mental gymnastics and oftentimes self-sacrifice if they felt like they were working towards something inherently good. At this point, it’s progressed beyond just looking good, but feeling and being good. A goal enshrined in a distorted moral code informed by calories and sacrifice. The presence of this ritualistic behaviour in the service of aesthetics speaks to something deeper: our society’s obsession with corporeal worship.

We venerate the body, but only in certain forms. We don’t idolise it as it is, but as what it could be if we were better. In the process, we risk erasing what the average woman and the average human look like, isolating those who go against the grain simply for existing.

fin

SkinnyTok didn’t invent these behaviours; it merely rebranded them for a new generation. Unhealthy habits have lost their stigma and are made palatable through aesthetics, filters, and curated feeds. Behind the curtain, a growing industry profits from our insecurities. Until we break the systems that uphold these beliefs—rewarding control, punishing appetite—SkinnyTok will simply grow another head or take on a new disguise.

Its popularity, fueled by algorithms that lust for controversy, signals a public health crisis. The canary is choking, and the mine is collapsing. But with collective intervention, structural change, and compassion at every level, we might still find a way out of the tunnel.

Hey guys, what did you think of this week’s essays . I enjoyed the process of writing it from the background reading, to watching it turn out the way it did. I really do think my favourite/best essays lead with a central question. I did not come up with the title on my own. I’ve got to give credit to the following creator and tiktok who asked the question in a video:

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

As usual happy to discuss anything in the comments!!

See you next week

As per usual, you can find me on TikTok, Instagram (daily media recommendations) and Arca (curated recommendations)

You can check out this month’s episode of What My Brain Eats here:

What My Brain Eats with Salome

Hey guys, welcome back to another episode of What My Brain Eats with this week’s guest, Salomesdiaries!! WMBE is the show where my guests and I take a deep dive into the media shaping our lives.

this was so beautifully crafted and handled with such care and empathy. thank you for writing a piece like this because it feels so validating, especially in the season that i’m going through. 🫶